Every time someone asks Debbie Beaver where she’s from, she has to shake her head.

When she answers, “I’m Canadian,” there’s the inevitable followup question: “OK, but where are you really from?”

“It still irritates me to this day,” said the administrative assistant in the University of Alberta’s Department of Psychology, who co-founded the Black Settlers of Alberta and Saskatchewan Historical Society in 2005 along with other descendants of Black settlers.

“My family has been here for more than 100 years, but there are so many people who are totally unaware of that history.”

Few are aware, for example, that there was a small but thriving Black community in downtown Edmonton in the middle of the 20th century.

At its heart was Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn—where the provincial court now stands—a popular meeting spot for musicians and celebrities, such as famed singer and trombonist Big Miller, American singer Pearl Bailey and young local music legend (later Canadian senator) Tommy Banks, who visited regularly to soak up the culture.

“I interviewed Banks before he passed away,” said Beaver. “He used to hang around at Hatti’s to hear the music when he was just a teenager,” she said. “That's where he got his love for (jazz) music and got to know Big Miller.”

“When Black people were barred from other establishments back in the day, they could eat there … Hatti’s was open from about noon to five in the morning—long hours.

The restaurant was owned by Hattie Robinson, born in 1903 and raised in the Amber Valley area north of Edmonton, one of a handful of early 20th-century Black settlements.

Hatti’s is just one of several stops Beaver highlights on her Black history walking tour—part of a larger, international event called Jane’s Walk. Held in May, it encourages people to “share stories about their neighbourhoods, discover unseen aspects of their communities and use walking as a way to connect with their neighbours.”

A century of history in Alberta

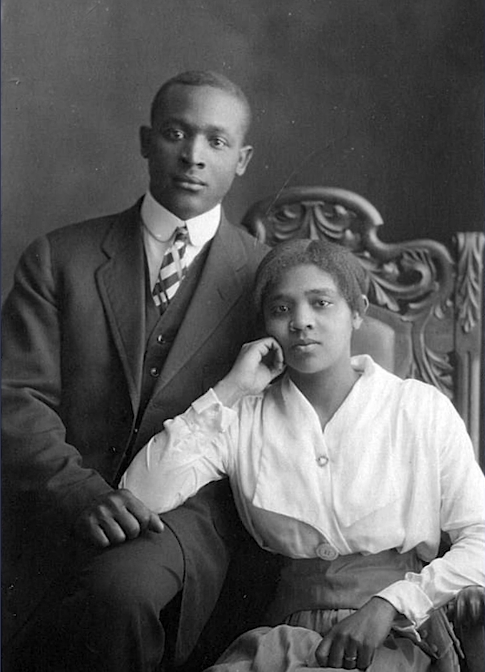

Beaver is herself a fourth-generation descendant of slaves. Her great-grandparents on both sides escaped racial persecution in the American south by fleeing to Canada in the early 20th century.

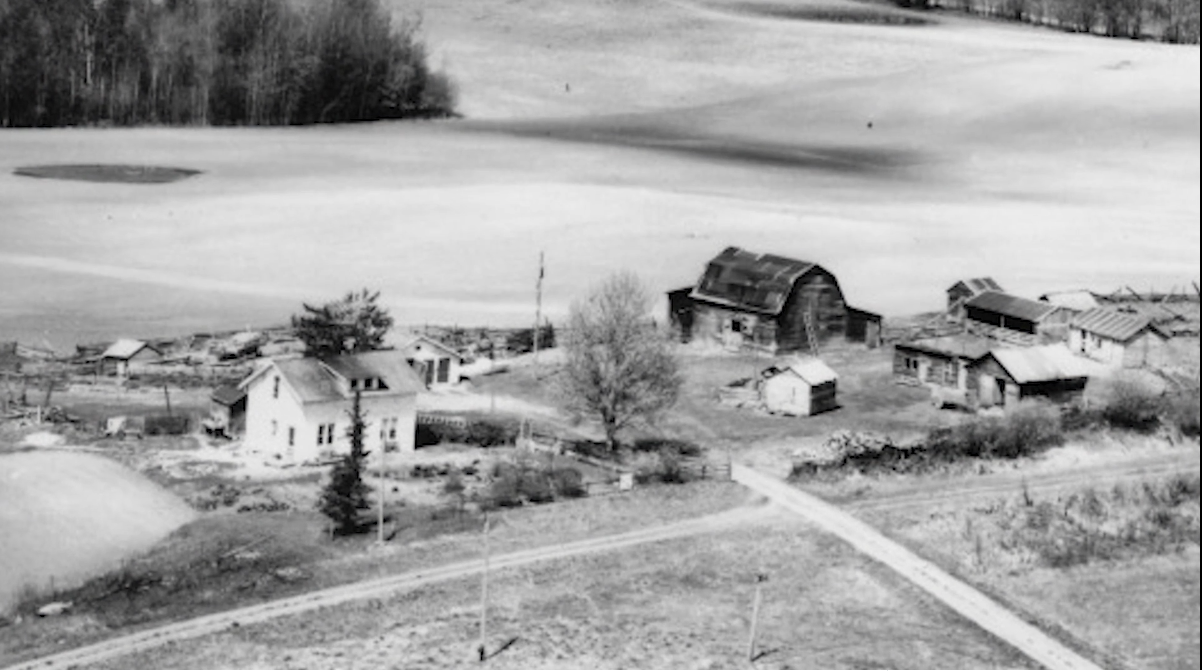

Her paternal great-grandparents arrived with a group of 40 refugees, and settled in Campsie, Alberta, near Barrhead. It was a mixed-race community with about 10 Black families at first, growing to about 50 by the 1920s.

Others settled in the communities of Wildwood, Amber Valley, Campsie and Breton. Some migrated to Maidstone in Saskatchewan.

“My great-grandparents actually dug a hole in the ground and covered it with logs. They lived in that for the first year they were here,” said Beaver. “I can't imagine how they did that.

“My father ended up farming on the same homestead that my great-grandfather cleared. And that's where I grew up … I was the first Black child to go to the local school (Littleport in Tiger Lily).”

The house her grandparents lived in is still on the original homestead.

Preserving stories for future generations

Beaver’s society has filmed about 45 interviews with those who still recall those early days. She hopes to produce a documentary film when the team secures funding.

Two years ago, the society contributed research to a Royal Alberta Museum exhibit on western Canadian Black settlements. Part of that exhibit, which ended in November, will remain in the museum’s permanent collection.

Beaver was also interviewed for a documentary called We Are Roots, about the discrimination suffered by Black settlers in the West.

Perhaps the best known of those settlers was John Ware, the “Black cowboy” born into slavery, who left South Carolina after the American Civil War and eventually made his way to Alberta. The local legend was one of the first cowboys to settle in southern Alberta, introducing longhorn cattle to the province and doing much to lay the foundations for future ranching.

"Ware is the best documented and well known, but our goal is to make people aware that there were others, especially those Black women who settled here and also have great stories.”

The society has also been working recently to encourage school boards in Alberta to integrate those stories into social studies curriculum.

“They need to continue to be told, preserved and passed down to the future generations, as this is an important piece of Canadian history,” she said.