Margaret Atwood was only seven when she got her first bitter taste of literary rejection.

She wrote a play called “The Giant, the Gost (sic) and the Moon” and staged it with paper puppets and a cardboard set. It conveyed the weighty themes of lying, crime and punishment “as befits a future novelist,” recalls the author.

“The play was panned by the critics. My brother and his pals laughed at it, thus giving me an early experience of literary criticism.”

So Peggy, as she was called then, turned to long-form narrative with “Annie the Ant.” Here she was on firmer ground, since her father was an entomologist. She wrote one story, in which Annie is swept downriver on a raft, and planned a novel as sequel, only to quickly lose interest.

“As a page turner, it leaves a lot to be desired, since ants don’t do much until the fourth stage of their lives, lacking legs as they do before then,” she said.

As the world now knows, those early literary aspirations did eventually bear fruit. Atwood has since become Canada’s most celebrated author, with 17 novels—many released to international acclaim—10 collections of short stories, 16 collections of poetry and seven works for children.

Three of her novels have been adapted for the screen, and the television version of her 1986 novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, garnered both Golden Globe and Emmy awards for best television series.

Her debut novel, The Edible Woman, was published in 1969 while she was teaching at the University of Alberta as a sessional instructor. By then the juvenilia was long forgotten.

It remained so until 2007, when after her mother’s death Atwood found a steamer trunk in her mother’s basement containing a treasure trove of stories and drawings by both Margaret and her brother Harold.

Some of that juvenilia is now available to the public for the first time in a volume co-edited by U of A professor emerita of English and film studies Nora Foster Stovel, and Donna Couto of the University of New South Wales, Australia.

Containing fiction, drama, verse and some of Atwood’s childhood illustrations, Early Writings by Margaret Atwood is published by the Juvenilia Press—founded at the U of A in 1994 by professor emerita of English Juliet McMaster.

Stovel came across the collection in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto while doing research for her book Divining Margaret Laurence.

“It's really quite delightful and childish,” said Stovel. “We retained all the original misspellings, and there's a really good sense of humour, which I think is an element of Atwood's writing that’s not sufficiently appreciated.

“There’s also an emphasis on animals in her early writings, especially cats,” she added. “She has always had cats, but as a young child she wasn’t allowed to have animals because the family was moving around too much.”

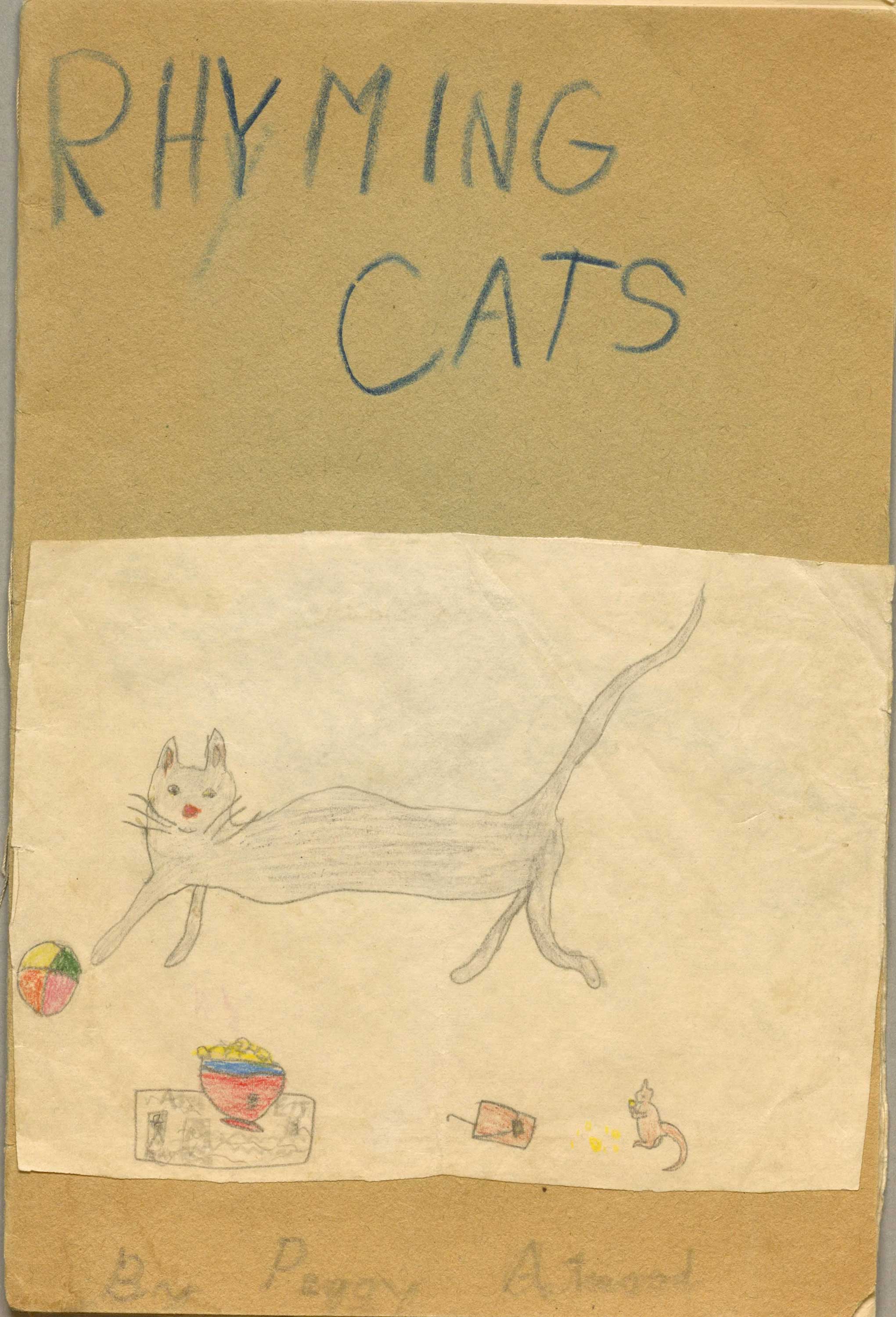

Rhyming Cats, a collection produced when Atwood was six, contains 26 short, rhyming poems with titles such as “Cats,” “My Dog,” and “When I Grow Up.” One gem called “Fairies” displays characteristic self-referential humour: “Fairies come at magic times,/ and they make such magic chimes./This rymes (sic).”

In high school Atwood wrote two operettas, one a “subversive act” for her home economics class designed to avoid an assignment sewing stuffed animals. She convinced her teacher to allow the class to perform an operetta instead. The teacher agreed, as long as it had a home economics theme.

And so it did. Called “Synthesia,” a satire on the new synthetic fabrics of the time, it features a king and queen who have three daughters—Orlon, Nylon and Dacron. Atwood played Orlon, married to Sir William Wooley, who suffers from the unfortunate condition of shrinking when washed. Atwood the satirist was born.

From class project to publishing house

The Juvenilia Press started as an extracurricular project for McMaster’s English students in 1992. She had them edit and annotate Jane Austen’s childhood story “Jack and Alice,” written when the British novelist was 13.

The hobby project eventually evolved into a small publishing house, operating on a shoestring budget, mostly with volunteer student labour. To this day, it is devoted to introducing students to publishing skills.

One of the students in her 1995 Jane Austen class was Winston Pei, who has since designed a number of works for Juvenilia Press, including Early Writings by Margaret Atwood.

“It’s been a joy to me for over 25 years now,” said Pei. “As the designer, I kind of feel like the conductor of an orchestra—I get to pull everyone’s contributions together into a performance, a piece of music, for a new, bigger audience.”

Since 1995, the press has published 68 volumes, including the early work of such luminaries as the Brontës, George Eliot, Charles Dickens and Canadians Rudy Wiebe, Greg Hollingshead, Margaret Laurence, and Carol Shields.

McMaster handed over the reins to Christine Alexander at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, 18 years ago, but it remains the only press in the world producing scholarly editions of juvenilia.

Early Writings by Margaret Atwood is the second volume of Atwood’s juvenilia published by the press, which in 1997 released two of her short stories and a poem written at 17 under the title, A Quiet Game.

Childhood charm

Atwood spent two years at the University of Alberta between 1968 and 1970 as a sessional instructor in the Department of English while her husband at the time, Jim Polk, was on faculty. That’s when she met McMaster.

McMaster recalls serving on an exam committee with Atwood for a student who had produced a novel for a creative writing master’s degree.

“It was known she was something of a writer then,” said McMaster. “Remember, this was pre-Edible Woman, but she wasn’t allowed to vote on the exam because she wasn’t on faculty.

“The following year I was in England during my husband Rowland’s sabbatical, and I remember seeing a review of Edible Woman in the Times Literary Supplement, so I sent it to her.”

It was years later when McMaster approached Atwood to contribute material for A Quiet Game. She said that while it was “good, conscientious teenager stuff,” it doesn’t have quite the same charm as the current volume.

“This gives you the childhood creativity—it's amazing. Her mother kept everything, and some of it is pre-literate. Margaret would draw pictures and sing songs about them, and her mother would take notes on the story behind the picture. I just found it fascinating.”

Atwood’s assessment of those early attempts isn’t quite so glowing.

“They’re pretty bad, actually, by any objective standard,” she admitted at the book’s launch in late November.

“But you have to believe they’re good, don’t you?”