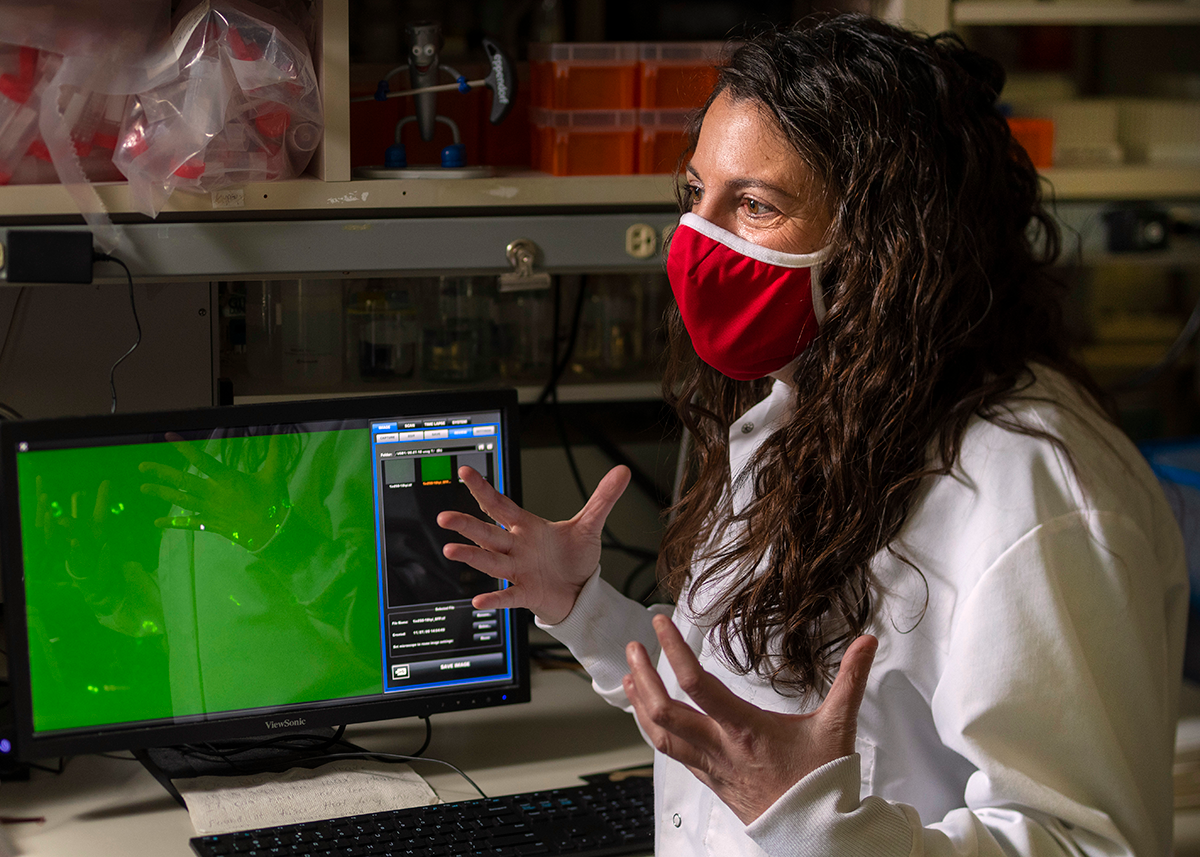

It was a chance conversation with a colleague in chemistry that led University of Alberta virologist Maya Shmulevitz to the glow-in-the-dark eel protein, a discovery that is advancing cancer therapy in a new way.

It’s common practice for researchers to use fluorescent proteins to track how viruses behave inside a cell. But the usual proteins are too large for reovirus, a powerful virus that fights some kinds of cancer.

Shmulevitz and her lab spent two years perfecting how to insert the tiny green eel protein into the reovirus. Now, researchers who study other viruses all over the world are using the same technique.

“That’s the beauty of science—nothing progresses alone,” Shmulevitz said. “Now we are replacing the green protein with all sorts of other small things that will power this virus as a cancer therapy, and potentially even a vaccine.”

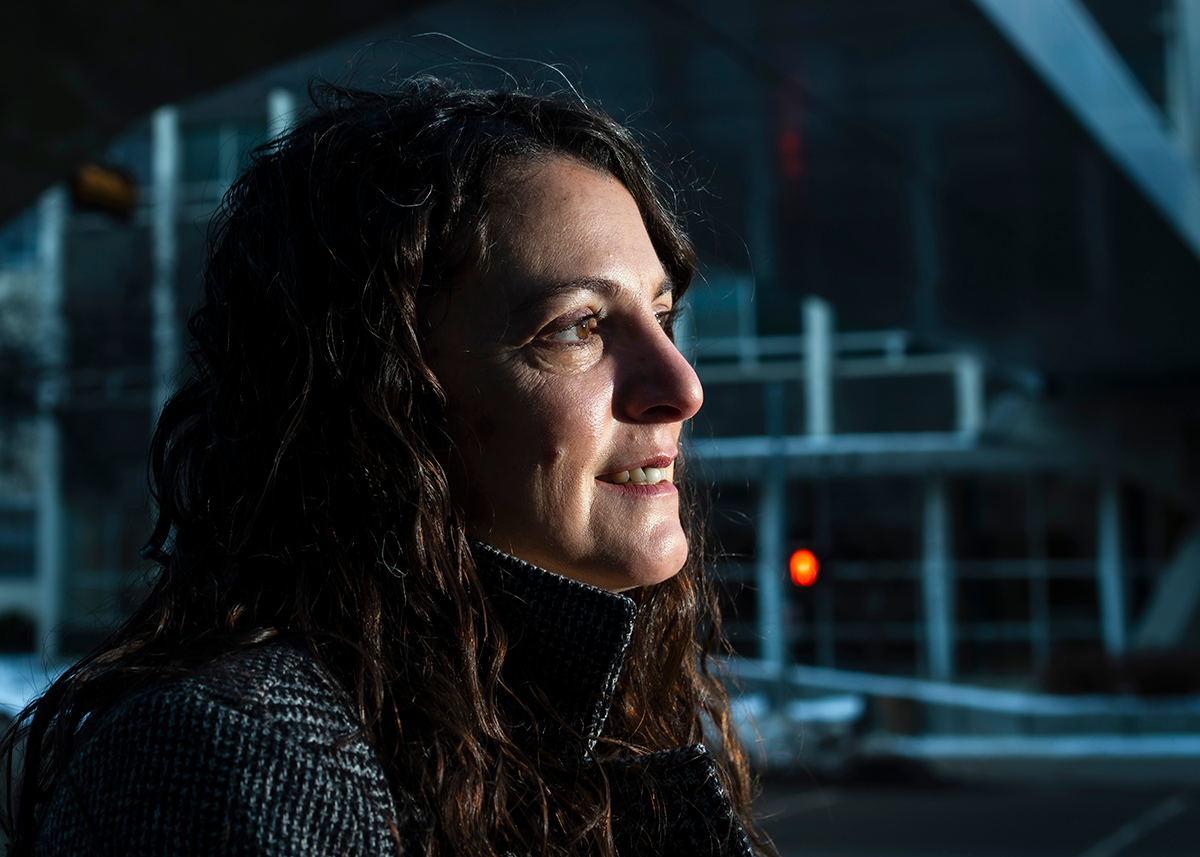

Asking the right questions and working with the right collaborators are the keys to success in virology, said Shmulevitz, Canada Research Chair in Molecular Virology and Oncotherapy and associate professor in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry.

As U of A virologist Michael Houghton prepares to accept his Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine on Dec. 10, Shmulevitz and virologists David Marchant and Matthias Götte talked about the impact their colleague has had on their science, and how the world can benefit from the big questions being asked in U of A labs.

Collaboration is key: Maya Shmulevitz

Shmulevitz sums up working with her U of A collaborators this way: “The mind is always more powerful when there are multiples.”

“It’s the combined power of all the virology research that makes it such a positive,” she said. “There can’t be a silo.”

Scientists from the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology, the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, and other disciplines from across the university regularly present to one another, inspiring new approaches.

“For example, last week there was a presentation from engineering about a method to stretch apart molecules, and I can apply that in my viral work,” Shmulevitz said. “I listen to every seminar and think, ‘How can I use that knowledge in some way?’”

Shmulevitz is one of several U of A researchers focused on understanding viruses that attack cancer cells but leave normal cells alone. She is working with one virus, oncologist Mary Hitt with another, David Evans with yet another. Rather than competing, these different approaches complement one another, Shmulevitz said. These types of combination therapies, or “cocktails,” have proven highly successful in controlling HIV.

“In the past we’ve used just one drug to fight a cancer or a bacterium, but then it evolves its way around our treatments,” she said. “The challenge is that no one lab is going to come up with five approaches that can be combined, so it requires group work.

“We need five different ideas that will work together — that’s the future.”

Shmulevitz, who grew up in Edmonton, earned her bachelor of science degree at the U of A. Her graduate studies took her around the world to Chicago, Israel, Saskatoon and Halifax. She was going to “let the wind decide” where science would take her next, when virology “superstar” Michael Houghton was recruited to the U of A in 2010 with a newly created Canada Excellence Research Chair. Shmulevitz jumped at the chance to come back to her hometown.

“This was an extremely exciting place in Canada to set up a virology lab,” she said. “It was the largest number of virologists in a single space. … At the U of A, the potential is limitless.”

Going commercial: David Marchant

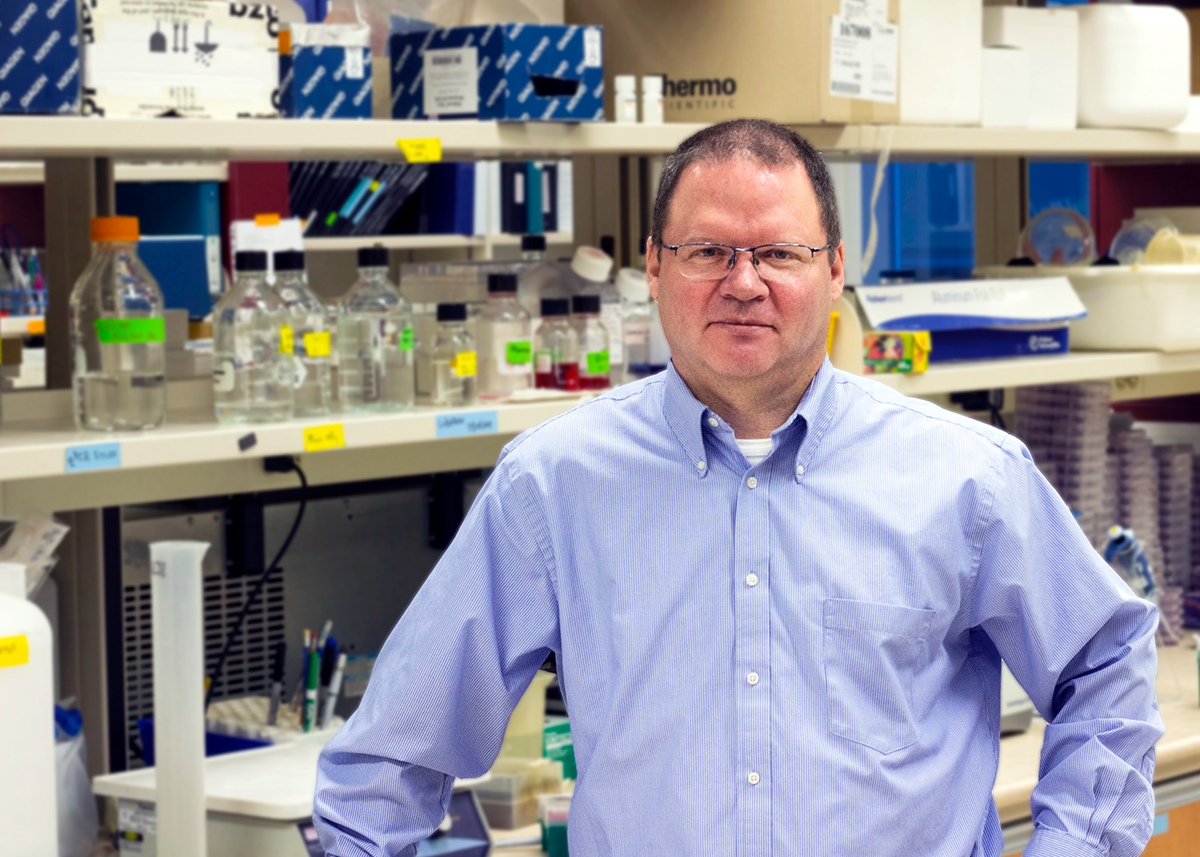

It was the unique opportunity to commercialize virology discoveries that attracted David Marchant to the role, thanks to the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute headed by Houghton.

“I wanted to help with the search for therapeutics and better ways of diagnosing infections,” said Marchant, now an associate professor of medical microbiology and immunology and Canada Research Chair in Viral Pathogenesis. “It behooves us in this day and age to commercialize our discoveries, not just pursue science that is neat but not necessarily useful.”

Before coming to the U of A, Marchant made a major discovery to understand the cause of a common childhood illness. His team determined how respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) gets into a cell, causing pneumonia, serious lung disease or even death in some infants. Marchant’s paper was published in the prestigious academic journal, Nature Medicine, the day of his job interview with the U of A. “Luckily enough they could look it up,” he recalled.

Fast-forward to June of this year when Marchant’s team published in Nature , this time identifying a second receptor or “doorbell” that RSV uses to trick cells into letting it enter. Marchant has formed a company with other U of A scientists. They have received federal funding to develop an antiviral nasal spray called RespVirex in collaboration with researchers at McGill University in Montreal and the Pasteur Institute in Dakar, Senegal.

RespVirex shows promise against dengue and RSV, and Marchant is hopeful it may have an impact against SARS-CoV-2. Effective in the laboratory and some animal studies, the drug has not yet been tested in humans. The goal is to make a nasal spray that could help protect against infection, perhaps in combination with drugs that target other parts of the virus.

And the spray has potential to protect against viruses we haven’t yet uncovered.

“It would help to have a broad-spectrum antiviral [during outbreaks such as COVID-19] where even if you haven’t identified the pathogen, you can protect those who are most vulnerable,” Marchant said.

Every step of the way, his senior colleagues have provided guidance.

“Michael Houghton rode in on his white horse a number of times with advice and direction—for example, with patenting strategies,” Marchant said. “It’s been so helpful to be part of this virology community.”

Aiming for higher goals: Matthias Götte

Matthias Götte was an undergrad at the Max Planck Institutes in Munich when Robert Huber won a Nobel Prize in chemistry for his part in a discovery related to photosynthesis. The excitement inspired Götte to continue his own studies in science. He’s thrilled to see the same inspiration uplift U of A staff and students as Houghton accepts his Nobel Prize Dec. 10.

“It motivates all of us at the university to aim for these higher goals—to ask the right questions, work on significant problems and find solutions,” said Götte, whose work focuses on some of the world’s most lethal viruses: Ebola, Lassa and coronaviruses.

(Photo: Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry; taken before COVID-19)

“As a scientist, you’re focused on the nitty-gritty. It’s very detail driven, but it’s important to keep an eye on the big picture, too,” he said. “The work that Michael Houghton did on hepatitis C saved hundreds of millions of lives and paved the way for the discovery of the potent antivirals that actually cure the infection.”

Götte, professor and chair of the Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, said U of A scientists have made invaluable contributions to the fundamental understanding of how viruses and cells interact to allow infection—knowledge critical for the discovery and development of antiviral drugs and vaccines.

It’s work that is now paying dividends as many U of A researchers turn their focus to SARS-CoV-2. Since the pandemic hit, researchers at the university have received funding to undertake 181 projects, including in virology.

Whether the next challenge facing humankind comes from cancer, antimicrobial resistance or another viral pandemic, U of A researchers will be ready to take it on.