Slow down a sec. University of Alberta computing science grads want to show you something.

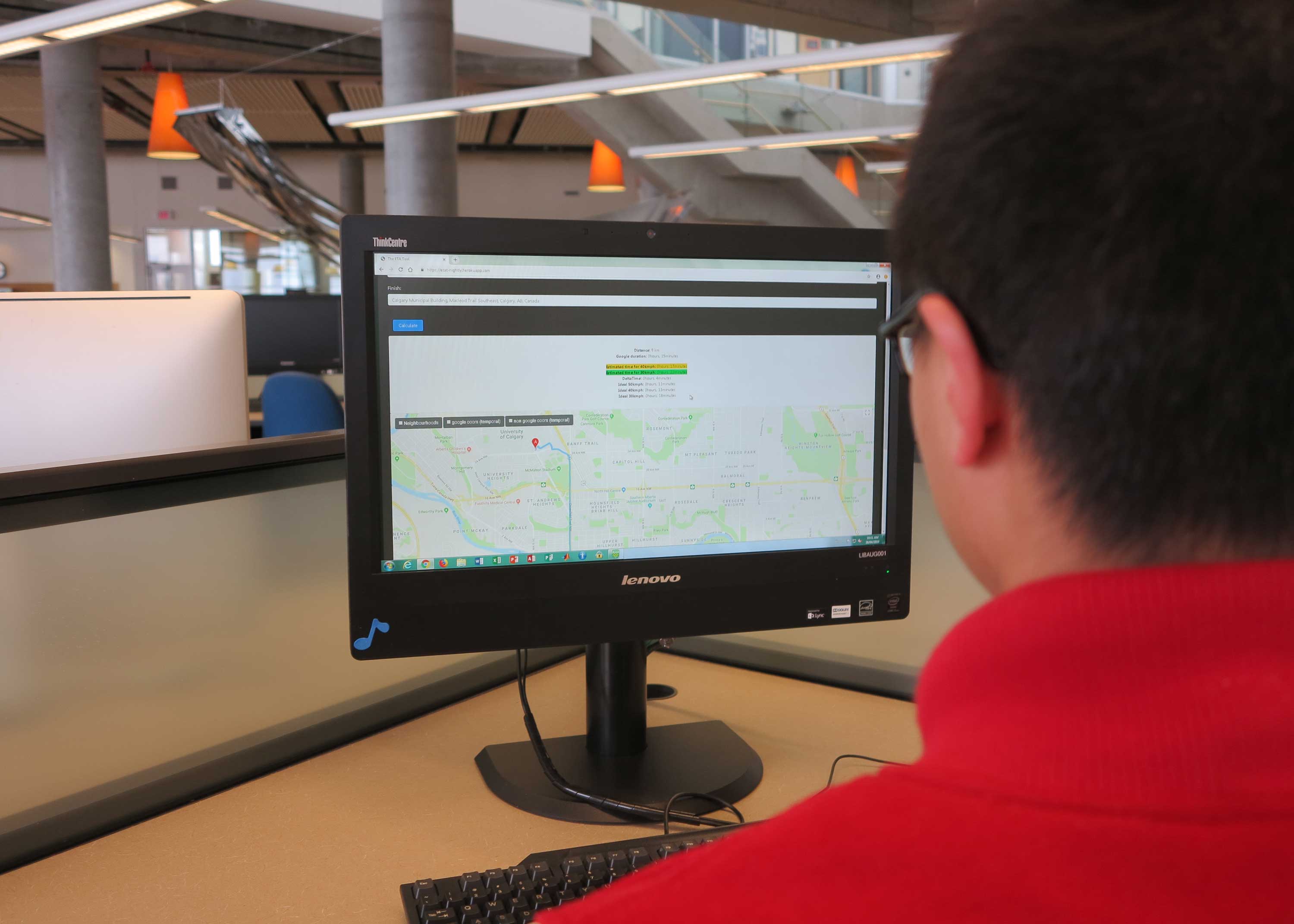

Students from Augustana Campus developed The ETA Tool, a web-based app that is being used by the municipalities of Edmonton and Calgary to let drivers know just how little time they would lose travelling anywhere in their cities if residential speed limits were reduced. Simply punch in point A and point B and you’ll get a number for any time of day.

Prepare to be surprised. Going 30 or 40 km/h through your neighbourhood probably won’t hold you back more than a minute or two. In the most extreme scenarios, it could add five minutes to your trip.

“What happens is that you get out of your driveway, and quickly you’re onto a high-speed road,” said Peter Zung, one of a trio of U of A alumni who helped create the app before they graduated. “During rush hour, you can’t go 50 anyway because of the traffic.”

The ETA tool was first developed by Zung and his classmates, Fatima Bin Sumait and Phil Nadon, along with Ronny Maichle from the University of Calgary, for competition in a 2018 Hackathon hosted by the City of Calgary.

Zung had researched speed limits long before the annual coding competition, which challenges teams to build solutions over the course of a weekend. Facing a challenge around pedestrian-friendly apps, he pitched a simple idea to his teammates: why not quantify how much time drivers really lose by slowing down?

They didn’t win the competition, but city officials saw potential in the idea and approached them afterwards. The tool, which builds on Google Maps data, could help put the rubber to the road on debates about speed limits as municipalities across Canada mull changes, encouraged by studies that show a drop in speed could dramatically cut down on the severity of pedestrian collisions.

Making a case for public support

Though traffic experts are convinced a policy change could save lives, convincing the public to hit the brakes isn’t ever an easy sell. The ETA Tool could help make the case.

A skeptical public might shrug when they hear injury statistics, but could listen more closely if they can measure how a change will affect them personally, Zung said.

“Half of the job is to find out the solution; the other half is to convince people that you have the right solution. People hear statistics all the time. They’ll say OK and forget about it or hear it or maybe they’ll be doubtful.”

“It’s a great message to deliver,” said Jen Malzer, the City of Calgary transportation engineer who worked closely with Zung and his classmates. “There’s a lot to gain by slowing down, but many Calgarians might worry about how much it’ll add to their busy schedules. This puts a number to the idea.”

Calgary has averaged nearly one pedestrian injury every day, according to one study, with a fatality roughly every six weeks. Motorists were to blame in just over half of the cases, meaning that proper use of crosswalks is no guarantee of safety.

City administration encouraged Zung’s team to build a beta version of their prototype and resubmit it for consideration. It resulted in a contract for the team to maintain the ETA website for Calgary, and eventually, a deal to develop and maintain a similar tool for the City of Edmonton, which came onstream in 2019.

Malzer agreed the tool could be used elsewhere and shows the value of opening city data for public collaboration.

“We also feel this tool could help other cities,” she said. “It really shows the power of public expertise and working collaboratively.”

The team hopes to expand use of the tool to other communities, said Nadon, who added he and his classmates believed enough in the project to power through its challenges.

“We faced serious roadblocks to the point where we weren’t sure we could do it, but we kept pushing. We knew this tool was really important because it was an unbiased way to show how much of an impact lowering speed limits can have.”

Learning by doing

Rosanna Heise has taught computing science at Augustana Campus for nearly three decades, and while she’s had many bright pupils over the years, she’s never seen students run so far with an idea.

“It’s quite incredible,” she said. “It was a lot of motivation on their part to seek it out and to follow it through to the end. I’m very, very proud of them and impressed with what they’ve done.”

Heise loves how the ETA Tool could take emotion out of traffic debates. But she also believes it could help city planners virtually any time they need to make an individual case for a lower limit.

Given the demands of creating a beta version, Heise worked with the students to create a guided practicum course to transform their idea into a full-fledged app. She added daily logging, a presentation at an academic conference and a final reflection paper, steps that helped the students move ahead while inching closer to graduation.

The results are a vindication of a project-based approach to courses, Heise said. She routinely gets software engineering students to build Android apps by their second year, moving up the complications each semester. The real challenge, she said, is conceptualizing a problem in a way that’s solvable with computing.

“They used their computation skills to attack what some people wouldn’t consider a problem for computing skills,” Heise said. “Students need to be able to engage with disciplines and abstract ideas out of that.”

For Zung’s team, the experience has been bigger than putting the computing science training to use. In addition to the feverish work to complete assignments and graduate, he learned intangible lessons about managing budgets, balancing workloads and dealing with lawyers.

For his part, the hard work Nadon put into the project is paying dividends in his career as a software engineer.

“This was my first real-life project, and the mistakes and right choices I made taught me a lot about project management and setting timelines. I’ve taken these lessons and applied them to my current work.”

After all the work, and having graduated, Zung relishes the fact that the ETA Tool has gone public. But there are no plans to slow down.

“After Calgary, we can work with other cities,” he said. “In college, a lot of the stuff you learn is theoretical. But this was where we had to apply something to the real world.”

Great ideas change the world, but ideas need a push forward. At the University of Alberta, we know that push has never been more important as we do our part to rebuild Alberta and keep doors of opportunity open to all. We're making research discoveries. We’re cultivating entrepreneurs. And we’re giving our students the knowledge and skills they need to turn today's ideas into tomorrow's innovations. Read more stories about U of A innovators .