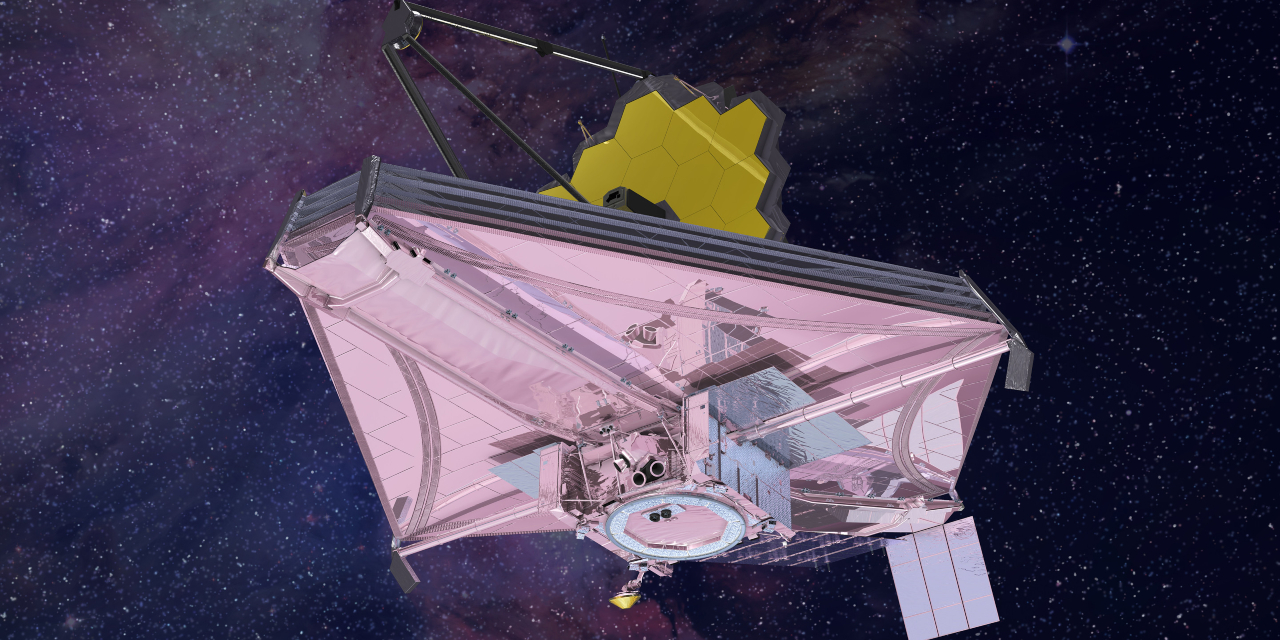

After 12 years of delays, NASA announced last month that the $10-billion James Webb Telescope was finally assembled.

The successor to the Hubble Telescope, which has been in orbit for almost 30 years, the Webb is touted by NASA as "the premier observatory of the next decade, serving thousands of astronomers worldwide" and transmitting images of "every phase in the history of our universe" while looking for signs of life beyond our solar system.

When it finally launches in March 2021, University of Alberta space historian Robert Smith will follow the Webb's every move, as he has done since the inception of the project more than 20 years ago.

Smith is recognized as the on-the-scene historian of this enormously complex collaboration among thousands of scientists at NASA, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency. As he did with Hubble, Smith interviewed key players, attended project meetings with astronomers and engineers, and carefully examined planning documents.

His two decades' worth of research will be published shortly after the telescope successfully reaches its destination a million miles from Earth. Once settled, its six-metre-long mirror will capture infrared images of the origins of the universe.

According to NASA, the Webb will peer into "the first luminous glows after the Big Bang, the formation of solar systems capable of supporting life on planets like Earth, and the evolution of our own solar system."

It's an ambitious mission with a huge price tag-double its original estimate. But it's also extremely high risk, because, unlike the Hubble, the Webb has "zero chance of being serviced; it will be just too far away," said Smith.

If it fails, the project will go down in history as one of the biggest blunders of big science.

Canadian connection

One key element of the Webb's design is a Canadian guiding system used to steer it to positions where it can best view distant galaxies.

"Tied in with that guider is an instrument that will search for planets outside the solar system," said Smith.

He points out that one of the most striking features in the story of space exploration-and one not always acknowledged-is the pervasive Canadian contribution. At almost every turn there is a Canadian scientist or engineer who has helped steer the course.

The space race of the 1960s is a case in point, as Smith recounted last July in a commemorative article published in the Literary Review of Canada to mark the 50th anniversary of the Apollo moon landing.

"So vast was the American space program in the early 1960s, so rapidly did it expand … that skilled engineers, managers, scientists, computer programmers and technicians were in short supply," he wrote.

"As one exasperated Jet Propulsion Laboratory manager exclaimed, 'Where are the people who know what they are doing?'"

It turns out they were in Canada, said Smith, looking for work after production of the famed Avro Arrow-Canada's first supersonic fighter plane-was cancelled by the federal government in 1959.

Thirty-two of Avro's engineers joined NASA, including its chief designer, Jim Chamberlin, who became head of engineering for Project Mercury, NASA's first human space flight, and chief designer for Project Gemini, "the 'engineering bridge' between Mercury and Apollo that pioneered space rendezvous and docking techniques essential for a moon mission," said Smith.

After U.S. President John F. Kennedy committed the country to landing on the moon, "Chamberlin would help settle some of the key engineering debates that animated Apollo for the next several years over, among other questions, the best way to land on the moon," Smith said.

Another member of the Avro team, Owen Maynard, helped design the Apollo 11 craft "from a private analysis room just off the primary mission control room in Houston."

History of space telescopes

Smith has staked his career on documenting every phase of the Webb and Hubble telescopes over the past four decades. His first, award-winning book, The Space Telescope: A Study of NASA, Science, Technology, and Politics, was a groundbreaking contribution to space history and a New York Times Notable Book of 1989, exposing just how complicated, fiercely political and ultimately flawed big science can be.

In addition to several books on the Hubble, Smith has published books and articles on the history of cosmology in the 19th and 20th centuries, and on the discovery of Neptune in 1846.

Before arriving at the U of A in 1998, he was resident historian at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., where every day for 15 years he would enter the building and walk past two celebrated and inspirational milestones of space exploration: the Apollo 11 command module, Columbia, and a model of Robert Goddard's first liquid-fuel rocket from 1926.

Smith's five-decade dedication to space history recently earned him the 2020 LeRoy E. Doggett Prize from the American Astronomical Society, awarded biennially to an individual whose career has significantly influenced the field of astronomy.

"Smith has made his mark on the history of astronomy and space travel by bringing a skeptical eye and thorough research to the field," said Chris Gainor, president of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and a former doctoral student of Smith's who did research on the Canadian contribution to the space program.

"Smith's book, The Space Telescope, contains important insights about the rise of large-scale scientific programs in the 20th century, such as the building of the political coalition that made the Hubble Space Telescope a reality."

What's next

After the Webb takes to the sky, the next big space project on the horizon, and one Smith will be watching closely, is the Lunar Gateway, an international space station that will orbit the moon.

"It's seen as a stepping stone to colonizing the moon, or operating as a base of operations for Mars exploration," he said.

"It will also be an opportunity to land the first woman on the moon, hopefully within the next five years," he added.

Canada has contributed $2 billion to the project over 24 years, mostly to produce Canadarm3, the latest iteration of the iconic robotic arm.