Getting involved in research with URI

Catherine Tays - 16 September 2021

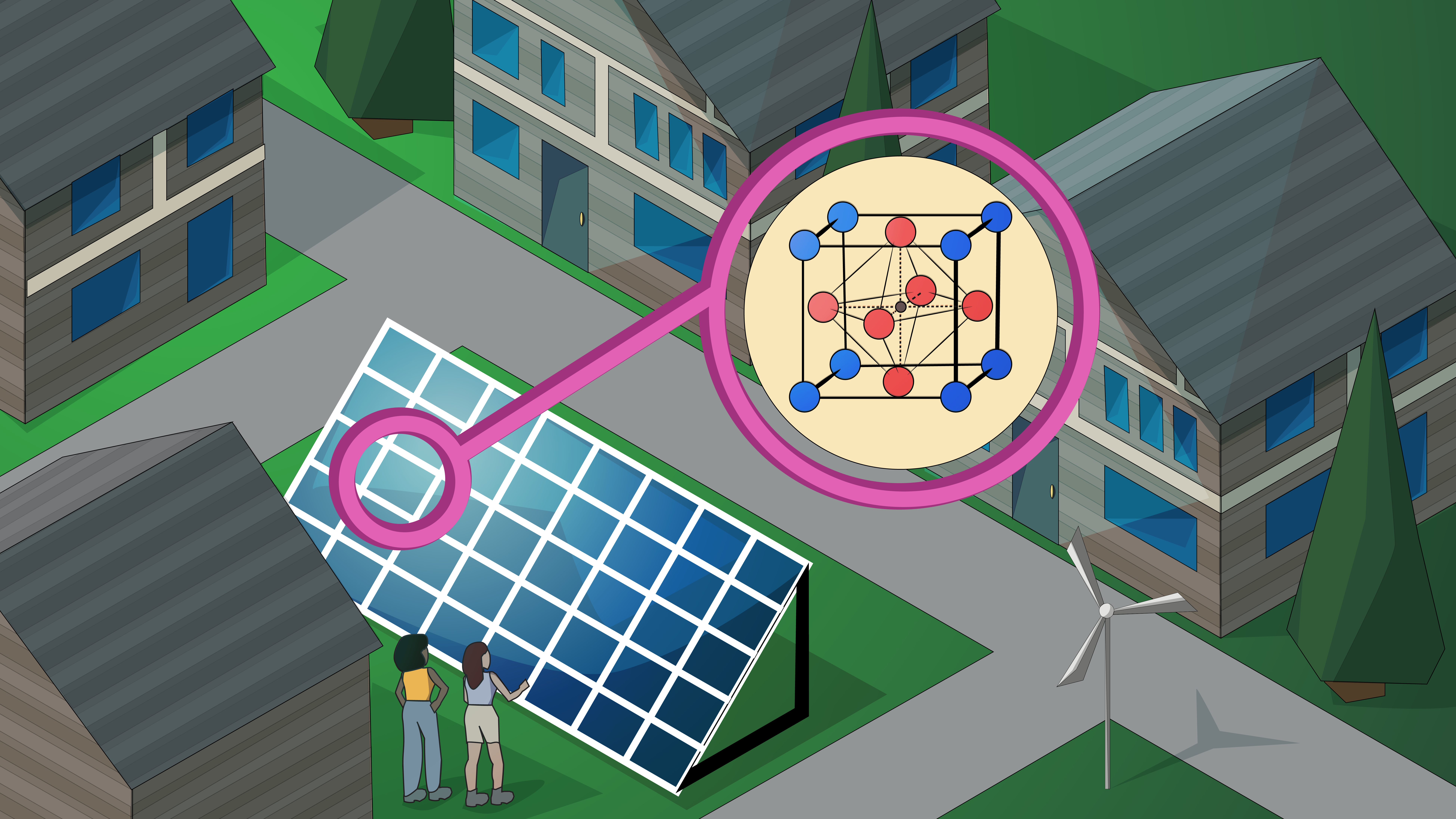

Over the summer of 2021, the Future Energy Systems Undergraduate Research Initiative fund sponsored Clarissa Gu to study renewable microgeneration and Katherine Lin to investigate perovskites for solar power (Illustration: Kaitlin Pylypa)

When you picture a ‘researcher’, what image comes to mind? Over the summer of 2021, Future Energy Systems undergraduate researchers Katherine Lin and Clarissa Gu, could answer that question by simply looking in a mirror.

Katherine reached out to professors across the University of Alberta in an effort to get involved in the world of novel materials research. It was her undergraduate chemistry professor –– FES Principal Investigator Vladimir Michaelis, Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry and Canada Research Chair in Magnetic Resonance of Advanced Materials –– who invited her to join his group in solar materials research.

Clarissa was driven by her interest in urban planning. FES Postdoctoral Fellow Neelakshi Joshi in the Urban Environment Observatory accepted her as a mentee working in community-focused energy systems research, with Dr. Robert Summers (Faculty of Science, ALES Sustainability Council) serving as her faculty sponsor.

Both Katherine and Clarissa’s excellent research proposals and drive resulted in their acceptance into the Future Energy Systems-sponsored stream of the UofA’s Undergraduate Research Initiative (URI) Stipend, which fully funded their research salaries over the summer of 2021. With the summer term now over, both undergraduates are finishing up their research, reminiscing on their time in their respective research groups, and planning for the future.

New materials, new experiences

Katherine finished her first year of undergraduate engineering in May 2021, and after a year of classes spent solely online, she knew she wanted to do hands-on work over the summer break.

“I wanted to do something meaningful,” she says. “I had never stepped foot in a lab before and I knew I was going to eventually, for my degree. So I thought I could get some experience first, before second year, by finding a lab to volunteer in.”

Katherine found job boards listing opportunities, then began contacting professors directly. “I would see research topics on their websites that sounded interesting to me, and email asking if I could get involved.” The process involved a lot of rejection: “I was still in first year, and I think a lot of professors need students with more technical experience, and more time in the lab. So that was a challenge for me, definitely.”

Eventually, Katherine connected with Vladimir Michaelis, hoping that he might be open to hiring her since she had taken his introductory chemistry course. “I think it helped to get an A in the course,” she laughs, “so he gave me a chance.”

The work that caught her attention was the development of novel materials for use in solar cells. “Clean energy has been around for a while, but it’s expensive and hard to maintain solar panels currently. It has to be marketable,” she explains. “It’s so important that we switch to something sustainable for our earth.”

Prof. Michaelis agreed to accept her in a part-time, volunteer position, and suggested that she apply to the URI Stipend so he could take her on full-time over the summer. When Katherine was awarded the FES-URI award, her work began in earnest.

Over the summer, Katherine used a technique called solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to characterize novel solar cell materials. Her work focuses on a class of materials called perovskites, which could be a big upgrade from the silicon standard used now. Through NMR, Katherine assessed what the perovskite materials look like and how quickly ions can move within these compounds –– information that can help researchers determine how efficient new materials are for use in solar cells.

Day-to-day, Katherine found research to be a creative and challenging space. “It can be three days trouble-shooting how to set up the NMR, and it can be days running a series of experiments that take 20-90 minutes for each data point. Some days it just works. It’s very flexible, depending on your project and the day,” she says.

That fluidity motivated Katherine over the course of her research term. “At first, I tried to treat it like a normal 9-to-5, but that’s not what it is. It’s a great environment to learn by yourself, and I still had a friendly team and a mentor to rely on,” she says, “But to keep changing and adapting like this –– it’s really engaging.”

Community-driven, personally-motivated

When Clarissa received an email from her fourth year urban planning instructor, Neelakshi Joshi, requesting expressions of interest for a URI-funded research project, she knew she had to respond.

“I’ve been interested in urban planning for quite a while. It’s something I spent a lot of time learning and talking about,” she says. It was by watching videos about street layouts and transit pathways that her interest really emerged. She began trying to find the reasons for Edmonton’s development decisions, asking questions and discussing planning with her friends. “They tell me I should just start a YouTube channel already and stop telling them about it,” she laughs.

When the URI opportunity arose she already had a myriad of potential research questions and proposals to send back to Neelakshi. One was the idea of sustainable housing, and the various ways in which higher energy efficiencies and lower emissions can be achieved.

“There are many ways to reduce our carbon footprint through housing –– using electricity generated from renewable sources instead of fossil fuels, for instance,” she explains. “Today, lots of people are looking for ways to generate electricity in their homes –– microgeneration, it’s called –– but there’s a lot to consider when making that transition.”

Clarissa identified a number of different sources of energy, including solar, wind, geothermal, and biomass, and her research involved evaluating which sources are most useful in which situations, and why.

“There’s lots of factors that affect energy use and needs. I looked at the factors that people are most concerned about,” she says. Those factors included cost, environmental impact, reliability, lifestyle compatibility, and energy production potential. “Some people are willing to sacrifice their yards by excavating it to install the pipes for geothermal. Others can dedicate themselves to the higher maintenance required for biomass. It’s not the same for everyone,” she explains.

By digging through online resources, including virtual tours and interviews of citizens who had re-fitted their homes for microgeneration, Clarissa was able to pull together a large, curated archive of information about microgeneration suitability and the factors at play for making those decisions about installing and living with microgeneration in their own homes.

She quickly realized that many people lack access to important information to help make those decisions ––a general overview of the steps involved with installing microgeneration was available from government sources, but it was generally up to the consumer to create a cost benefit analysis for all the renewable energy options. To address that knowledge gap and help people get the most out of their residential energy transition, she created a blog incorporating the information she had curated, which is soon to be hosted on the School of Urban Planning website.

“I would love to work in sustainable housing, and there’s so many other areas that are fascinating too, like transportation and gender equality in urban planning,” Clarissa says. “It’s just great to be able to build something that people can use and rely on.”

The Undergraduate Research Initiative

Even today, as progress in diversity and inclusion has started to spread through the academic world, the age-old image of the ‘old boy’s club’ continues to partially define research. This is a challenge in most research fields, but it is especially pronounced in the areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

In its 2016 census data, the Government of Canada reported that STEM fields account for over one-third of men’s bachelors degrees (37.5 percent), compared to just 15.3 percent of women’s. The government also reported that women leave STEM occupations for non-STEM occupations at higher rates, and generally do not return, showing that even increasing undergraduate enrollment is not sufficient to overcome this gender gap. It has also been shown that participation and persistence in STEM fields is lower for Indigenous individuals or those with a disability.

That’s why the University of Alberta and Future Energy Systems continue to introduce and support programs that welcome and perpetuate the presence of underrepresented voices in research. The Undergraduate Research Initiative (URI) is one such effort, specifically funding research salaries for women, students with disabilities, and First Nations, Metis and Inuit (FNMI) students, enabling them to pursue research in a University of Alberta laboratory or group.

Katherine and Clarissa are happy to offer advice to future applicants seeking to launch their own URI journeys.

“Start applying early, as early as you can,” Katherine says. Since a lot of grant applications are due in January, she recommends contacting professors in the fall, so there’s more time to find funding to support the work. “It was probably more challenging for me because I was a first year, but I was able to find this opportunity because I kept trying.”

“Find something that you really want to work on –– it has to be something that you care about so that you keep motivated and excited about it,” Clarissa says. “I was really interested in urban planning, so it made it difficult to stop myself from going off tangents, but that means there are still so many things I want to keep researching and looking into, even after this summer.”

If you or someone you know is interested in pursuing a career in STEM or gaining your first experience in research at one of Canada’s premier research universities, the 2022 intake of URI applications will open this fall. Click here for more information.