Boots on common ground

Kenneth Tam - 31 January 2019

Future Energy Systems PhD students Kylie Heales and Maggie Cascadden.

If an energy company is selling you an environmental solution, are you skeptical of its promises? Your answer probably depends on how much you trust the company and, especially in recent years, trust has not been universal.

Energy companies seeking to meet social and regulatory obligations to reduce their environmental footprint need the support of communities to take action, but even assuming the best solutions are being proposed, community trust isn’t something that can be guaranteed with a budget line-item. Flyers can be dropped, ads can be bought, and consultants can run town halls, but if people in a community don’t feel meaningfully engaged, implementing solutions can be impossible.

As co-lead of the Future Energy Systems Land and Water theme, Alberta School of Business Professor Dev Jennings and his team are working to develop an engagement framework to help companies and communities find common ground. His test case: constructed wetlands.

Naturally-occurring wetlands –– in Alberta, sometimes called sloughs or potholes –– are complex ecosystems that cleanse water, sequester carbon, and promote biodiversity. Environmental engineers at the University of Alberta and elsewhere are working on designs for artificially constructed wetlands that can be customized to decontaminate water affected by energy production.

Unfortunately, wetlands in Alberta can be contentious. For years the provincial government paid farmers to drain them in support of agricultural production, but more recent policies have protected wetlands and even required their restoration. When combined with controversial energy questions and concerns about constructing artificial environments, wetlands promise to stir emotions on many sides.

A framework that companies and communities can adopt to reach consensus about constructed wetlands could be applied to many different types of energy projects, but for it to work it cannot just be theoretical; it must reflect the real experience of people on the ground.

Fortunately, the students who have joined Jennings’ team understand natural resources are always about people –– and know where to go to find common ground.

Trading suits for jeans

Kylie (far right) with her team at the Queensland Farmers' Federation (in suits).

In 2015, Kylie Heales was climbing out of her car among the lush green cotton fields of one of Australia’s richest agricultural regions, roughly two hours outside of Brisbane. She was an advisor for the Queensland Farmers’ Federation, and she was wrangling a delegation of policy experts, researchers and farmers who were working on policy about coal seam gas exploration. Agricultural producers needed a say in energy development in one of the country’s richest croplands, and the best way for them to be heard was obvious to Kylie: ditch suits for jeans and drive decision-makers out to farms for candid conversations.

“Business and policy decisions are based on a constellation of factors,” she explains. “First-hand experience talking to people who work the land, and want to protect the land, can be bright stars in that constellation.”

Having grown up in Mackay –– a coastal Queensland city surrounded by intensive agriculture –– Kylie was at home among the cotton fields. She knew what it was like when the pre-harvest clearing drove anxious rodents into her house and school. She understood the appeal of running cattle on thousands of acres, and how important irrigation was on a continent where water is precious. As a trained economist, she also knew policy could often run against on-the-ground experience, causing strife that could have been avoided by better engagement.

“You can’t force people to see eye to eye,” she says. “But when you create constructive opportunities for them to look each other in the eye, you give them a better chance to find common ground.”

Finding common ground between people, especially with respect to environmental and social issues, is a focus for Kylie. Her research partner shares that determination.

Hip-deep in a wetland

Maggie (right) planting willow stakes at Pine Lake. Photo courtesy of the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Around the same time Kylie was guiding researchers through cotton fields, Maggie Cascadden was hip-deep in a wetland half an hour east of Red Deer. Along with fellow Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) volunteers and staff, she had spent the day harvesting willow branches and preparing them like stakes to be planted on the last undeveloped quarter section around Pine Lake. Bundles of those stakes had be to carried into the middle of the wetland, where they would stay safe and alive until the next group of volunteers arrived to plant them.

“Many of us ended our day with wet boots and socks,” she recalls. “But those sorts of experiences really helped build cohesion in our volunteer team. They’re part of the reason we could learn so much from each other.”

As a volunteer for the NCC Maggie was introduced to a wide range of individuals. All of these people shared a passion for the environment, though many came from dramatically diverse walks of life with notably different views on how people should interact with nature.

“We had people who made their livings in the oil sands working side by side with pipeline protesters,” she says. “Because we were all there digging in the same mud, we literally had common ground –– and we had lots of time for enriching discussions about our own perspectives.”

These conversations, as well as interactions with landowners who partnered with the NCC to conserve natural lands, proved to Maggie the importance of real dialogue in creating effective working relationships. The principle applies to companies and communities as much as it does to people.

Understanding decisions

Experience working in Queensland and elsewhere convinced Kylie that businesses are usually the agents whose decisions have the greatest impact on social and environmental issues.

“Businesses are collections of people with vast resources and a coherent vision, and unlike governments they’re not bound by an election cycle,” she points out. “Influencing the way they operate can have a real impact on these issues, but in order to credibly influence their decisions you need to properly understand why they’re made.”

To better develop that knowledge, Kylie crossed the equator and completed her MBA at Duke University before joining the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for an internship in their agriculture division. As that post wrapped up, her gaze traveled north to Alberta –– an agricultural landscape with a massive energy industry that was grappling with its social and environmental impacts.

Seeing an opportunity to examine the interface between large for-profit businesses and their host communities, she joined the Alberta School of Business PhD program in the fall of 2018. Now she hopes to equip industry with the knowledge needed to conduct engagement in the best way possible.

“In my experience most companies are willing to engage with communities, they just don’t know the best way to do it, or how much time and money to budget to achieve benefits for everyone,” she explains. “With effective methodologies rooted in research, we have the chance to reduce uncertainties involved with engagement and improve the outcomes on all sides.”

Reconciling reality

Photo courtesy of the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Maggie came to the PhD program at the same time with a similar consensus-building goal. As an undergraduate at McGill University in Montreal, she encountered many fellow students who seemed to favor polarization over the more difficult task of finding common ground –– especially with respect to the oil sands. The unwillingness to engage with complex realities perplexed her.

“I grew up as a nature lover in a city that was prospering due to resource extraction, so I’ve always understood the tension between these competing priorities,” she explains. “Today’s energy systems have brought us incredible opportunities. We have done a lot of things well, and there are things we can strive to do better to make sure future generations can enjoy prosperity and a healthy natural environment.”

After a Masters in Resource Management and Planning at Simon Fraser University, she returned to Alberta ready to work on those tensions. She considered fields from environmental policy to political science, but like Kylie she determined that companies were on the front line –– especially in the oil sands. A business PhD hadn’t been on her radar, but as she became familiar with Jennings’ research she saw the chance to build a framework for finding common ground.

“I like talking about these issues one-on-one, but you can’t get thousands of people to put on hip-waders and help you drag willows out of a wetland,” she says. “Developing frameworks that facilitate the communication between larger groups of people with very different points of view is important work. It’ll just take some time to figure out.”

Fortunately, she and her partner are in it for the long haul.

Settling in

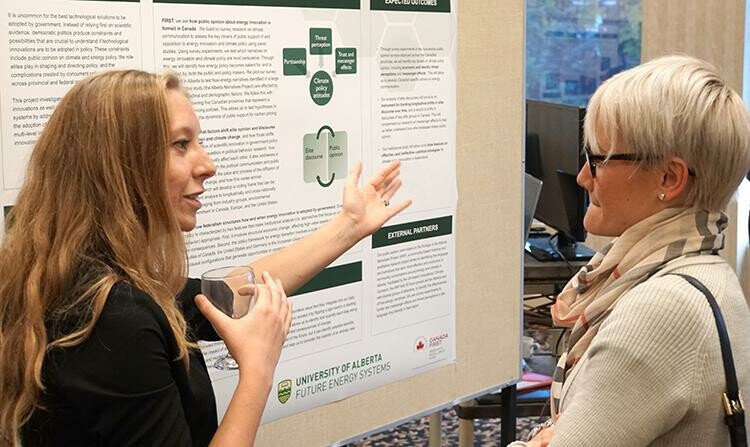

Maggie and Kylie discuss a poster at the Future Energy Systems Open House.

Just four months into their four-year program, Maggie and Kylie are still getting settled into their new home.

Having arrived in September, Kylie is still adjusting to the short winter days that come with Edmonton’s high latitude.

“I’ve been promised longer summer days, so I’ll plan some road trips into farm country to take advantage,” she laughs.

Maggie is trying to reconcile the fact that she sees so many Oilers jerseys on a daily basis.

“I’m from Calgary and have always been a Flames fan,” she shakes her head.

For the next eighteen months they’ll both be completing coursework as part of their PhD program, but plans for tackling the wetlands project are already taking shape. If companies and communities began considering constructed wetlands as solutions for contaminated water, what frameworks could help build consensus?

“Our first step is to look at wetland-related projects that have already taken place in Alberta,” Maggie explains. “We’ll review the literature and talk to people involved to get a sense about how these sorts of solutions are received by different types of communities.”

“After that we’ll test a few of the most promising methods for engagement,” Kylie adds. “Then we get to talk to people whose lives and livelihoods are shaped by their relationship with the landscape, to make sure we come up with a process that gives them a real chance to have their say.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, going out and talking to people promises to be the most exciting part for both of them. Road trips are already being visualized, and along the way there may be a few stops by sites that Maggie worked on during her time with NCC, so that Kylie can get a closer look at Alberta’s landscape.

“Water is so abundant here, I’m interested to see how people’s relationships with the environment are different than I was used to back home,” she says. “And I need to get a close look at some wetlands!”

Maggie smiles, “We’ll find you some hip waders. And a shovel.”

To follow the progress of this and other Future Energy Systems projects, subscribe for our newsletter.

To learn more about the project Resilient Reclaimed Land and Water Systems, click here.

To read stories about other Future Energy Systems graduate students, click here.