All we can reclaim

Kenneth Tam - 31 July 2018

Every spring when she was a child, Anne Naeth ran home from school and checked the bank of the North Saskatchewan River for the arrival of prairie crocuses so she could pick a few for her mother. Those fuzzy purple flowers would emerge from the snow on the south-facing banks, heralding the change of season on her family farm.

Eventually, her fascination with those plants led her to the study of plant biology and ecology, and then ultimately to the discipline of land reclamation. Even today, she slips the flowers into any presentation she can.

“People probably wonder what’s with the flowers in my slide decks,” she laughs. “It’s part of where I came from –– part of what got me to where I am today.”

Namely: what led her to be named the Director of the Future Energy Systems research initiative.

Without power

Childhood in Saskatchewan; prairie crocus flowers superimposed.

Anne’s family farm was near Paradise Hill, Saskatchewan, and during her younger years it lacked two things that she now relies on: running water and electricity. Sunset at home meant an end to any activities that couldn’t be managed by coal oil light, and washing and drinking was a chore.

“I didn’t realize what it was like to have energy in a home until my dad got the generator,” she explains.

Her father –– who’d never finished high school, but had taught himself how to build just about anything –– wired their house himself. Fortunately nothing burned down, and this new energy technology suddenly transformed each night into a time when reading was possible. Life changed.

“I learned firsthand the difference that being connected to a source of electrical energy can make. I really value having experienced the before and the after,” she says.

But as Anne adapted to the new life that electricity supported, she became increasingly aware of the impact energy production could have on the natural world that she cherished.

“The first time I saw an open-pit mine, I had a visceral reaction,” she admits. “When I connected what I saw in that mine to the electricity that let me read at night, it really was a lot to reconcile.”

Looking back now, she realizes that the early conflict between her love of nature and the value she placed on stable energy has helped define her career.

Peddling lies

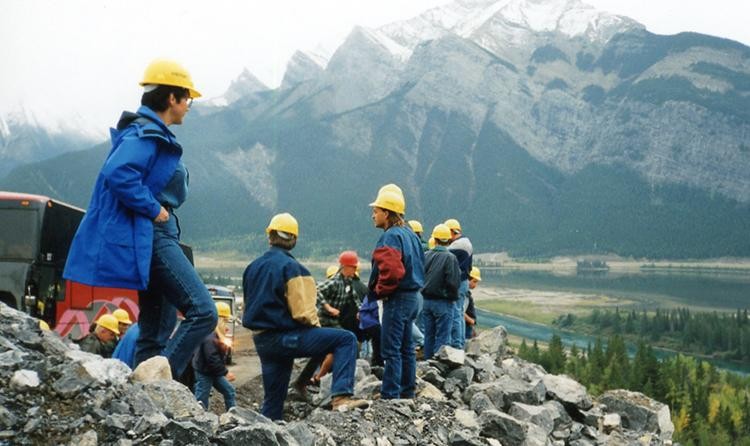

In the field with a group from the Canadian Land Reclamation Association.

The eldest of seven, Anne was the first of her family to attend university. Initially she was expected to be a lawyer or a doctor, but those plans were derailed when she took an elective course in botany. Understanding how her favorite plants worked was too interesting to pass up –– and that understanding came with the possibility of being able to help nature recover after human intervention. She completed both her MSc (the first graduate degree in land reclamation at the U of A) and PhD at the University of Alberta.

“My dad could take apart an engine, figure out how it worked, and put it back together. I wanted to do that with soil and plants,” she smiles. “My mom could look at a dress in a catalogue and sew one for me without a pattern. In reclamation we don’t have patterns either –– we see what was there before the disturbance and rebuild it.”

Putting disturbed ecosystems back together was a direct way to reconcile her love of nature and humanity’s need for energy –– she believed modern society could truly have both. But not everyone agreed that was possible, or believed that her motivation began in her love of prairie crocuses.

After giving a generally well-received dinner presentation to a group of bird conservationists about the viability of restoring habitat damaged by energy development, she received a scathing letter from a couple of attendees.

“They basically said I was the worst –– that I was peddling lies about being able to fix the damage, and that I was just giving energy companies an excuse to take what they wanted.”

The argument opposed (without evidence) years of her own research about reclamation, but what troubled her most was that it contradicted her own understanding of the world. She had experienced the arrival of reliable energy as a profoundly good thing –– albeit one with potent side effects that demanded attention. The letter proved that for some people the side effects of energy production could be of greater concern than access to the energy itself.

Still, she held her course: “I don’t think too many of us would enjoy life without the stability of the energy system we have –– unless people are more fond of coal oil lamps than I was.”

Unmaking messes

In 2013, LRIGS was recognized with the Canadian Land Reclamation Association's Watkin Award.

Anne’s focus remained fixed on helping nature recover more quickly and more completely from human intervention. Shortly after graduation she joined the Department of Renewable Resources in what became the Faculty of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Studies, where she is now a Professor and the Associate Dean (Research and Graduate Studies).

Her own research put her at the forefront of a growing field, and she also dedicated herself to award-winning teaching efforts that enabled new generations of students to start reclaiming landscapes around the world.

In 2011 she created the University of Alberta’s Land Reclamation International Graduate School (LRIGS) –– an NSERC CREATE-funded program that brought students from around the world to Canada to master the techniques of land reclamation. The six-year initiative was unique in the world, and she designed its program to focus on pragmatism.

“We can’t restore all sites to exactly what they were before we made the messes,” she confirms. “But we can get them to a safe and healthy state, then turn them over to nature –– and believe me, nature will figure out what to do with them.”

Much of the reclamation work done by LRIGS focused on resource extraction disturbances –– mining and oil sands sites being two of greatest relevance in Alberta. From analyzing soil types to understanding the importance of different insects to the health of an ecosystem, the school’s research explored the requirements of land reclamation and restoration in a comprehensive way. It also emphasized real-world scenarios, and provided practical perspectives on how research can change policy.

In that area, Anne drew on personal experience: she had been part of a team whose research changed government regulations for oil sands developers, requiring them to salvage the forest floor material they cleared from extraction sites so that it could be replaced during reclamation, thereby speeding environmental recovery.

“We were able to show how simple, low-cost actions before a disturbance could make a big difference after,” she says. “We worked with industry and government in a partnership.”

But again, the regulatory change was disregarded by some observers who viewed it as enabling an environmentally-damaging industry. The conflict between her love of nature and her appreciation for modern energy continued to be an undercurrent in Anne’s work –– and she doesn’t foresee that changing with the arrival of renewable energy technologies.

No favourites

Introducing the Future Energy Systems Land and Water theme to a delegation from the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres.

When it comes to renewable energy technologies, Anne plays no favourites. Reducing or eliminating the emission of greenhouse gases is a clear priority, but new systems may come with their own environmental side effects –– particularly if adopted at a global scale.

“If we rush to fix one problem but cause another, we’re not helping as much as we need to,” Anne says. “We expect a lot less disturbance from renewables, but we can’t casually assume that they just produce ‘clean’ energy, and not look at their impacts on nature.”

When Future Energy Systems appointed her as the head of its Land and Water theme, she set that foresight as a research priority. As a result, researchers are already looking at materials like chicken feathers as a means to remove energy-related contaminants from water –– regardless of what system produced them.

“Planning to deal with the impacts before we start building new systems makes a huge difference in reclamation,” she explains. “And figuring out what impacts we need to prepare for takes many different kinds of expertise.”

That’s why Anne has worked with researchers from multiple disciplines throughout her career. In LRIGS she involved academics ranging from resource economists to hydrologists to engineers, and for Future Energy Systems she partnered with co-leads Dev Jennings from the Alberta School of Business and Mohamed Gamal El-Din from the Faculty of Engineering.

“You can’t solve a problem you don’t understand,” she asserts. “And when you don’t have the knowledge yourself, you find partners.”

As an investigator within Future Energy Systems, she has appreciated the interdisciplinarity of the research group. Moving into the Director role, she looks forward to pushing the program’s groundbreaking collaborations to new levels, so that the entire scope of energy transition can be better understood.

And that understanding doesn’t stop with the environmental impacts.

The energy of many

The first annual Future Energy Systems Open House, October 2017.

The electricity that reached Anne’s childhood home came from a diesel generator. She hopes alternative sources can soon take the place of such systems –– solar fuels, wind turbines, geothermal engines or biomass reactors being developed as part of Future Energy Systems could one day power homes.

But if power were to come from the sun, the wind, the ground, or the nearby biomass, what would that mean for people?

“Suddenly you find yourself independent of a grid, and you don’t need to buy fuel,” she suggests. “If communities around the world stopped needing to buy fuel, what would that mean for the people in communities that exist to make fuel? What about the industries?”

To Anne, understanding the function of energy in society is principally the same as understanding the function of a natural environment. Diverse knowledge is needed –– understandings of the technology, the social context, the economic reality, and of course the environmental impact.

Over the past year, Future Energy Systems has launched nearly 70 projects that explore all of these issues –– and that’s why Anne took the Director job.

“We have more than 110 researchers and more than 310 students already working across this spectrum of issues,” she enthuses. “Now the exciting part starts: getting all of us talking together about what we know, and what that means for all of us.”

With the program’s administrative infrastructure now in place, Anne has set her sights on facilitating those interdisciplinary conversations. She’s keen to mix different perspectives about how the energy system works, how it impacts everyone, and what the future might hold. Drawing on her experience in LRIGS, she’s also determined to ensure that the program’s HQP –– hopefully more than 1,000 graduates by the end of funding in 2023 –– are well-equipped to go out into the working world, and make meaningful contributions to our energy transition.

“I’m going to be asking a lot of people to talk to people they’ve never met before, in disciplines they’ve never crossed paths with, about things they’ve probably only ever heard of,” she smiles. “None of us are in this alone –– that’s the exciting part. We’re all doing research because we care about the future of energy, the planet, and our communities. We can learn a lot from each other.”

For her part, Anne is already thinking about the presentations she’ll need to make to the research group.

She chuckles: “I wonder if anyone will notice the purple flowers in my slides.”

Handing off: outgoing Future Energy Systems Director Larry Kostiuk with incoming Director Anne Naeth.

To subscribe for Future Energy Systems updates, click here.

To learn more about Anne’s research project, Resilient Reclaimed Land and Water Systems, click here.