Rethinking the history of the Lakota of the Great Plains and challenging settler narratives

Chelsea Novak - 23 June 2022

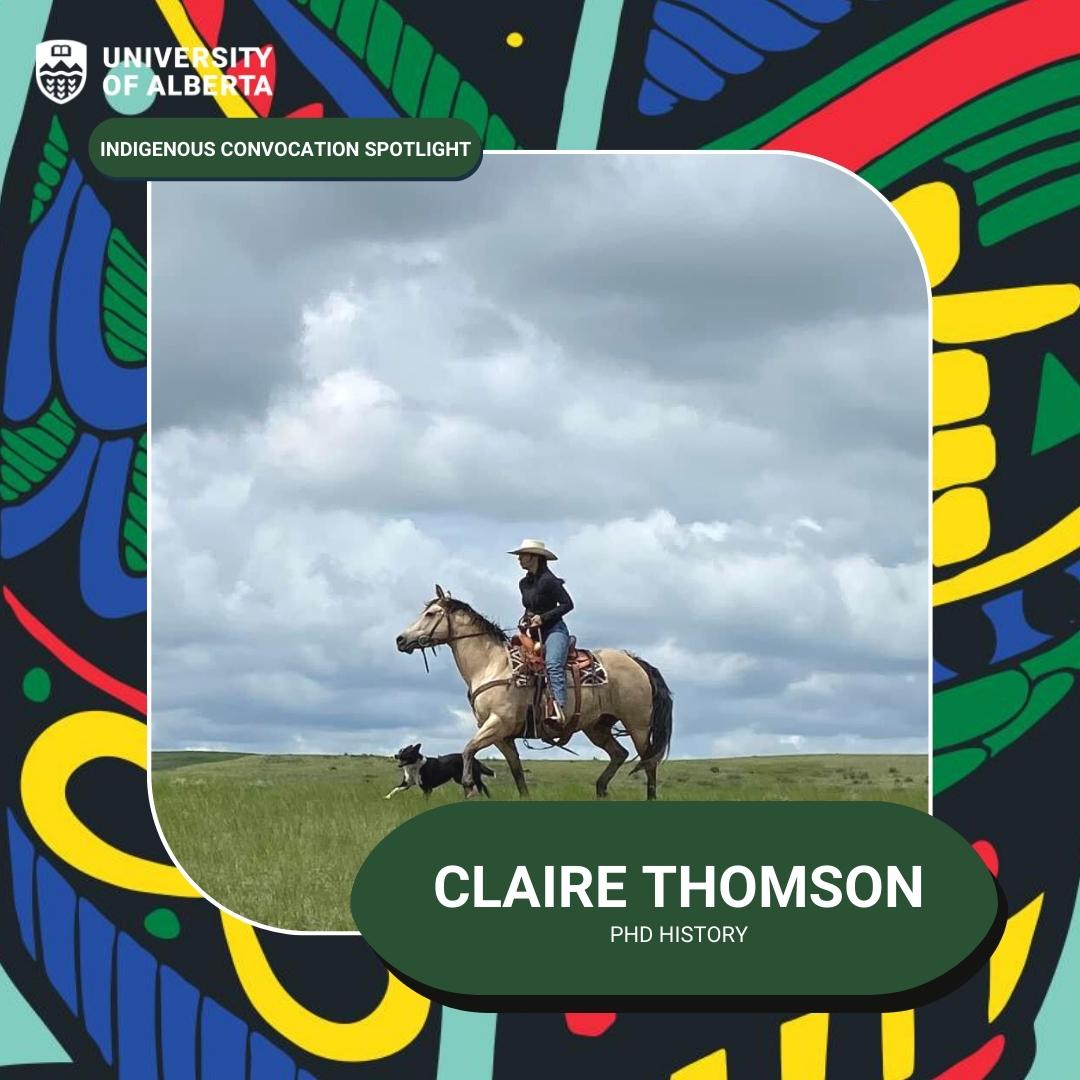

Growing up on a ranch in the Wood Mountain Uplands of southwestern Saskatchewan, Claire Thomson’s family history was always important to her. That interest led her to pursue graduate studies in History where she couldn’t help noticing that previous histories of the Lakota of the Wood Mountain Uplands all end with Sitting Bull returning to the U.S. in 1881.

“I knew that there was not a lot of literature or any kind of research about my community’s history, especially after 1881,” she says. “Any of the history that had been written was really American focused, was really focused on things like the Battle of Little Big Horn and the great chiefs and things, but nothing really about … how Lakota people came to what is now Saskatchewan.”

Thomson’s dissertation, “Digging Roots and Remembering Relatives: Lakota Kinship and Movement in the Northern Great Plains from the Wood Mountain Uplands across Lakóta Tȟamákȟočhe/Lakota Country, 1881-1940,” centres Lakota knowledge, language, kinship and community to deliver a path-breaking work of history that defies the myth of a vanishing culture. It breaks new ground by following the Lakota into the 20th century, focusing on their resilience and resistance, privileging voices outside of the male leadership, and highlighting the centrality of Lakota women to maintaining kinship networks. This incredible work has earned her not only a PhD from the Faculty of Arts at the U of A, but the Governor General’s Gold Medal, an honour her supervisor Sarah Carter says she more than deserves.

“She was just such a joy to work with,” says the professor and Henry Marshall Tory Chair in the Department of History, Classics and Religion and the Faculty of Native Studies. “She’s extremely curious and that just always leads her to dig deeper and deeper and deeper to find out what she’s curious about.”

Thomson began her graduate studies at the University of Saskatchewan in History and Native Studies, where she wrote a thesis titled “Lakotapteole: Wood Mountain Lakota Cultural Adaptation and Maintenance Through Ranching and Rodeo, 1880-1930.” While it specifically focused on the agricultural history of Thomson’s home community, it was a start down the path that would lead her to her dissertation.

Another important step for Thomson was learning the Lakota language. She spent a year at Oglala Lakota College in South Dakota, supported by a Fulbright Traditional Student Scholarship, learning the language so that she would be able to read letters she found in the archives.

“An important number [of archival sources] were written in Lakota, and I really wanted to not overload the few Elders that are out there that do translation work,” she says.

Thomson ran into some surprises while going through the archives, including a letter in the Lakota language penned by her own great-great-grandfather James Harkin Thomson for a Lakota man named Tȟašúŋke Ópi.

“I had no idea starting this that I would find so much family and community history, especially in big U.S. national archives,” Thomson says. “I had just no idea there would be that many family sources, not just my family but lots of local families that I know quite well.”

She adds that it was a privilege for her to be able to access those sources and share the documents with families from her community. Thomson also discovered that community members could provide their own historical archives, which Carter says contributed to “an excellent chapter” about photography.

“She found that photographs aren’t just taken by colonial photographers, but that there’s a huge wealth of Lakota family albums and photographs that circulated throughout the community across the Canada-U.S. border and kept them all informed about each other and kept everybody up to date,” says the professor.

Community and landscape both play an important part in Thomson’s framing of Lakota history, which focuses on kinship and the daily life of the Lakota rather than military events. She borrowed the term “kinscapes” from other Indigenous scholars to explain the connection between the land and relationships that is central to understanding Lakota kinship.

“[It’s] these networks of belonging, these networks of relating, and that relations aren’t just human, that they’re also to nature, they’re also to animals, there’s the supernatural,” she explains.

Thomson also takes a decolonizing approach by privileging the Lakota’s knowledge of their own territory and refusing what she refers to as “colonial containers.”

“One of her academic contributions is to challenge the borderlands approach to understanding the Great Plains,” says Carter. “The borderlands is looking at people who were bisected by the border … and she argues that actually confirms colonial borders and containers, and that we need to understand the Lakota concepts of what is their territory, their land and how they conceive of it.”

Having just received her PhD, Thomson plans to take a break from her dissertation before considering publication. In the meantime, she’s working as a historian for Parks Canada’s Indigenous Affairs and Cultural Heritage Directorate, continuing to learn Lakota, and farming and ranching at home with her family.