How Entrepreneurship Can Address Society’s Grand Challenges

This year, Angelique Slade Shantz, Associate Professor at the Alberta School of Business, received national recognition as the Canada Research Chair in Social Entrepreneurship. Chairholders like Angelique aim to achieve research excellence in order to deepen our knowledge, improve our quality of life, and train the next generation.

Angelique examines how businesses can address grand challenges, with a focus on entrepreneurship as a means of poverty alleviation. She employs a mixed methods approach, using field experiments and qualitative data, and often works in partnership with development organizations.

Prior to entering academia, Angelique worked in the field of social entrepreneurship and economic development, both internationally and in the context of Canada’s First Nations. She attended Arizona State University (BA), Duke University (MBA), and York University (PhD).

I had the pleasure of sitting down with Angelique recently to hear more about the evolution of her research and how it can help individuals, communities, and businesses tackle some of the world’s most pressing challenges.

First off, what motivated you to become a researcher?

A: People who were academics themselves were my primary inspiration to follow a path in research. One was Greg Dees, a professor at my alma mater, Duke University. Greg is widely known as the father of social entrepreneurship, or the idea that business can be used as a force for good. I was working as a social entrepreneur in Latin America at the time, but didn’t know there was even a name for what I was doing, let alone a field of academic study. I decided I wanted to get my MBA at Duke so that I could work with him.

I saw firsthand both the promise and the challenges of combining business with social change, and I knew I had a lot to learn.

While at Duke, I met another role model, professor Bob Clemen, who did research on the use of decision analysis to encourage organizations to become environmentally sustainable. Bob was not only a researcher, but also a great teacher, and he helped me to see the link between the two by encouraging me to pursue research, despite this being an uncommon pathway out of an MBA program.

A third influential figure was Anne-Marie Slaughter, who used her role as professor at Princeton University to advocate for equal opportunities for women, and particularly mothers who are also trying to balance a career. As a young mother myself at the time, her advocacy work resonated deeply with me.

These individuals demonstrated how researchers can have a big impact in the world, and this really inspired me.

You recently received the prestigious Canada Research Chair in Social Entrepreneurship. How do you see this award enhancing your research program?

A: In light of how the scholars that I’ve just described (and others) have used their platforms as academic researchers to have a positive impact, affect change, and influence ideas, I am hopeful that I can use the elevated platform the CRC gives me to do the same for other researchers.

Knowledge Translation

I also hope to use the CRC to focus more on knowledge translation. I always try to pursue research questions at the intersection of theoretical and practical impact, so knowledge translation is an area I hope to be able to enhance through the CRC, for example, through workshops, white papers, and articles in the media and more practitioner-focused journals.

Your research explores various different barriers to entrepreneurial activities, especially in contexts of resource scarcity. Can you give me some examples of these barriers, and how they might be overcome?

A. Yes, a lot of my recent work has focused on how social or institutional factors influence entrepreneurial behaviors among individuals living in contexts of extreme poverty. This is sometimes referred to as necessity entrepreneurship. In this area, I have explored organizational efforts to foster entrepreneurship (either collectively or individually) as a tool to address global poverty and inequality. Let me give some examples.

Social Barriers

In a publication in the Journal of Business Venturing, I examined social barriers to entrepreneurial innovation, which can reduce the effectiveness of entrepreneurship as a tool for poverty alleviation. Specifically, at our study location in rural Ghana, we found that beliefs about “collectivism” and “fatalism” featured prominently in the occupational identity of entrepreneurs, such that being an entrepreneur meant first and foremost being a mentor, market link, and community safety net – rather than being an innovator and job creator. Further, the types of opportunities entrepreneurs pursued were seen largely as predestined and inherited rather than individually identified. Ultimately, these features of entrepreneurs’ identities are barriers that can limit their ability to innovate and grow their businesses in ways that western entrepreneurship would expect, in spite of organizational efforts to support entrepreneurial growth.

Institutional Barriers

In another illustrative example, in a study recently published in the Journal of Management, my co-authors and I engaged in a nine-month mixed-methods field experiment involving 80 newly formed business co-operatives (e.g., farming) in Northern Ghana, where ethnic, tribal, and political conflict is deeply rooted. This conflict affects co-op members’ ability to work together to share resources and cooperate. We worked with the NGO that was supporting these co-ops to examine two different ways of framing co-op members’ behaviours: as avoiding conflict (prevention-focused) or as embracing peace (promotion-focused). For example, while a prevention focus might involve avoiding telling negative stories about others, a promotion focus might involve embracing telling positive stories about others. We anticipated that these different frames might help minimize conflict.

Our findings show that a prevention-focused approach, which prioritizes avoiding conflict, is more effective in reducing conflict.

Our findings show that a prevention-focused approach, which prioritizes avoiding conflict, is more effective in reducing conflict because of its resonance or ‘fit’ with the prevention focus that co-op members had already come to adopt, in the face of frequent and intense conflict within the broader environment. These findings have practical implications given the prevalence of intractable conflict situations affecting workplaces everywhere.

A secondary stream in your research program studies growth and degrowth in organizations. Degrowth is an interesting idea. What have you observed and what does research show here?

A: This is a newer stream of research for me. While my first stream of research examines how best to support entrepreneurs to facilitate upward economic transitions (out of poverty), this second stream questions the assumption that entrepreneurs exclusively seek upward economic transitions as their ultimate outcome.

Mindful Steps into Entrepreneurship

This line of inquiry considers the global COVID-19 experience that has surfaced existential questions about people’s participation in the workforce. I’ve observed that for some individuals, COVID-19 was an impetus to “try on” entrepreneurship, not because they were driven to act on an opportunity, nor out of economic necessity, but out of a search for meaning, environmental concerns, or as an act of protest – even when this can mean a downward economic transition, or what we are referring to as “occupational degrowth”. Research has yet to explore when and why individuals choose to transition downward into an occupation that is considered lower status, lower pay, etc.

At a broader level, recognized scholars are stating that the dominant belief among organizational and management scholars is that of the economic growth imperative. Yet, at the same time, concerns surrounding the earth’s carrying capacity are beginning to raise questions about growth as an ideology. Until now, these questions have been at a more abstract level. Research on individuals’ decisions about occupational degrowth makes these philosophical questions concrete, at the individual and empirical levels.

What grand challenges do you see your work as addressing, and how?

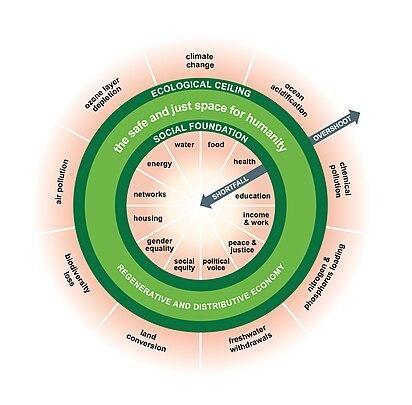

A: I like to use the economist Kate Raworth’s framework of “doughnut economics” to describe the two different streams of my research. If you picture a doughnut, those living in the middle (the hole) are those individuals or economies that are living below what we globally consider to be the social foundation – that is, those that struggle with basic needs such as food, clean water, literacy, basic health care, etc. Here we still need to see economic growth, to reach the inner edge of the doughnut.

Addressing Social Foundation Fundamentals

My first stream of research responds to challenges ‘inside of the doughnut” by trying to build knowledge about how best to support entrepreneurship (as one tool, but certainly not the only tool) to help lift individuals and economies to “get onto the doughnut”.

On the other hand, the outer edge of the doughnut represents the ecological ceiling, beyond which if we keep growing we risk air and water pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate change.

Addressing Ecological Ceiling Limits

In advanced economies and among the world’s wealthiest, we are pushing that limit, so my second stream of research seeks to understand how we might reconceptualize entrepreneurship as a tool to achieve meaning, satisfaction, and quality of life, rather than perpetual growth, in an effort to, again to use the metaphor, “stay within the doughnut”.

What words of advice would you offer to current or aspiring enterers, based on these streams of research?

A: Entrepreneurs have an important role to play in helping us to stay in the doughnut! While the doughnut is, of course, a somewhat playful metaphor, I find it to be a useful tool to help guide our thinking as we all try to navigate what business and entrepreneurship that is responsive to grand challenges can look like.

Article written by Sarah G. Moore (Associate Dean Research and PhD Program) and Deanna Hoffman (Research Coordinator) at the Alberta School of Business at the University of Alberta. More on Canada’s Research Chair Program.

Field research conducted by Associate Professor Angelique Slade Shantz in Ghana. (Photo supplied: Angelique Slade Shantz)

Read more about Angelique Slade Shantz and her latest research.